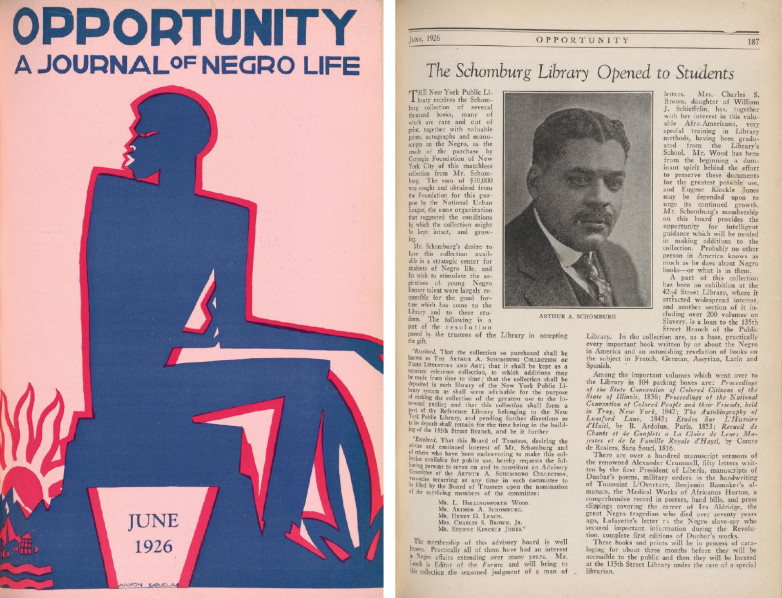

In anticipation of the Schomburg Center’s centennial, I became increasingly interested in its symbiotic relationship with this influential periodical. For instance, the Carnegie Corporation contributed $8,000 to help launch Opportunity; similarly, funds were given to purchase Schomburg’s collection for the library. Schomburg contributed several articles to Opportunity, including “My Trip to Cuba in Quest of Negro Books,” published in 1933 when he was curator of the Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints, a position he undertook in 1932. Gwendolyn Bennett, a poet and graphic artist who organized poetry readings and book discussions at the 135th Street Library, also wrote a monthly literary column for Opportunity from 1926 to 1928 called “The Ebony Flute,” a “literary and social chit-chat.” In the November 1930 issue of Opportunity, a twenty-year-old Fisk University student named Lawrence D. Reddick contributed a personal story called “Mister Charlie!” about his repeated harassment by two cops on his way home from his job at a coffee shop. Reddick became the curator of the Schomburg Collection after Schomburg’s death in 1938.

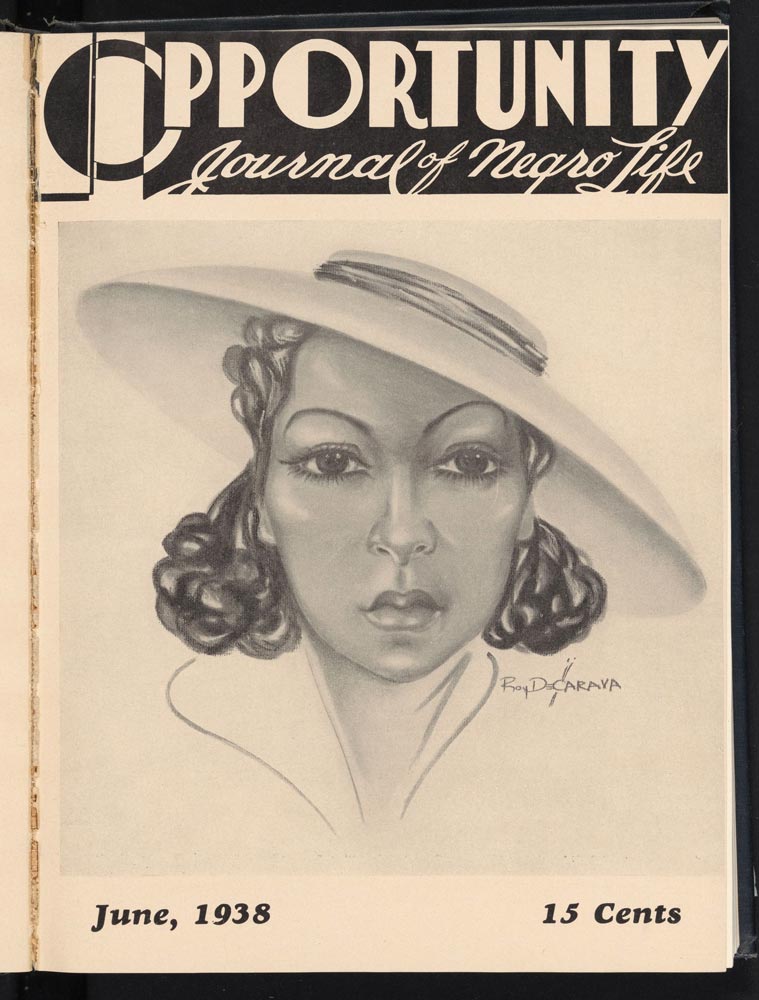

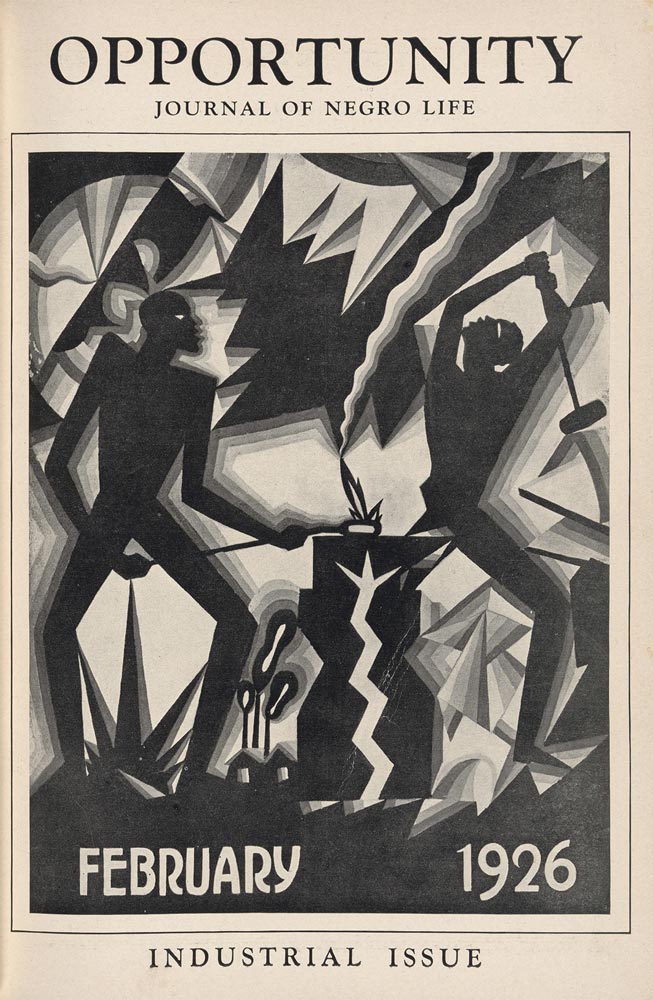

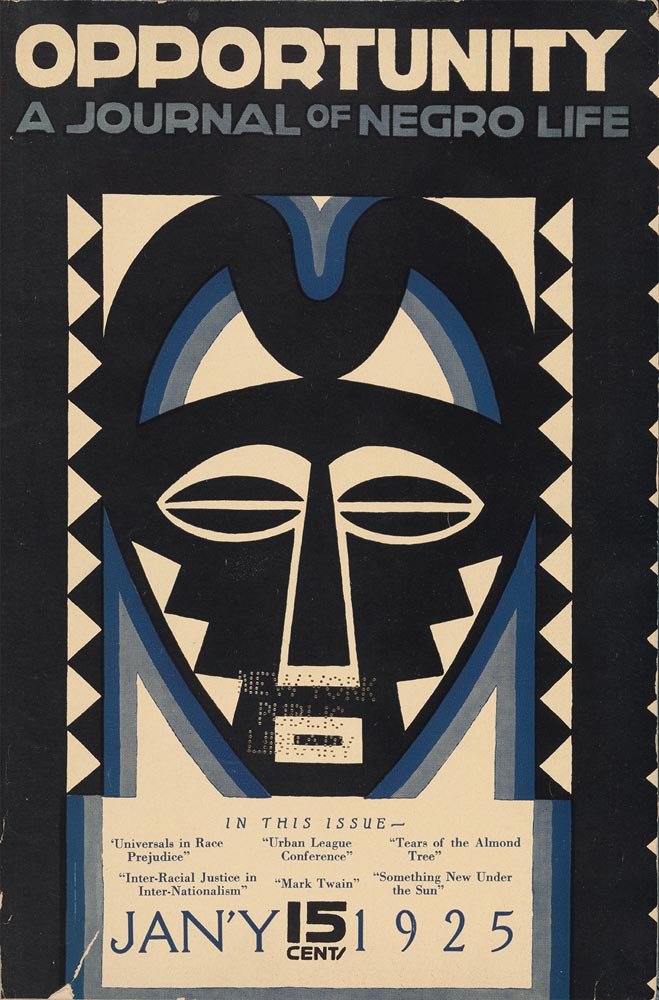

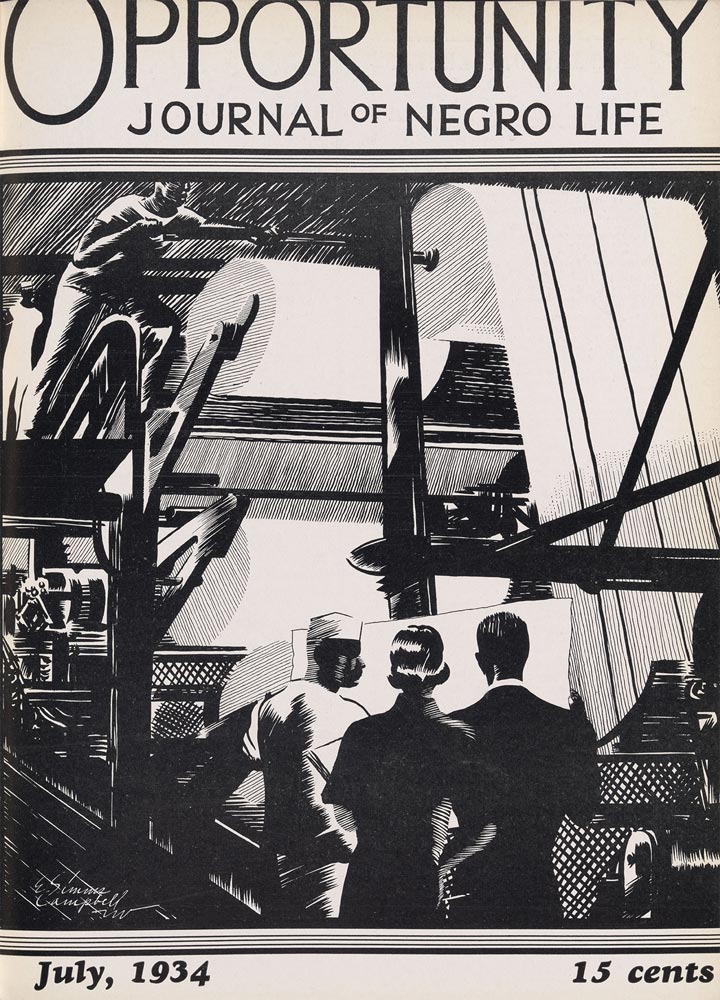

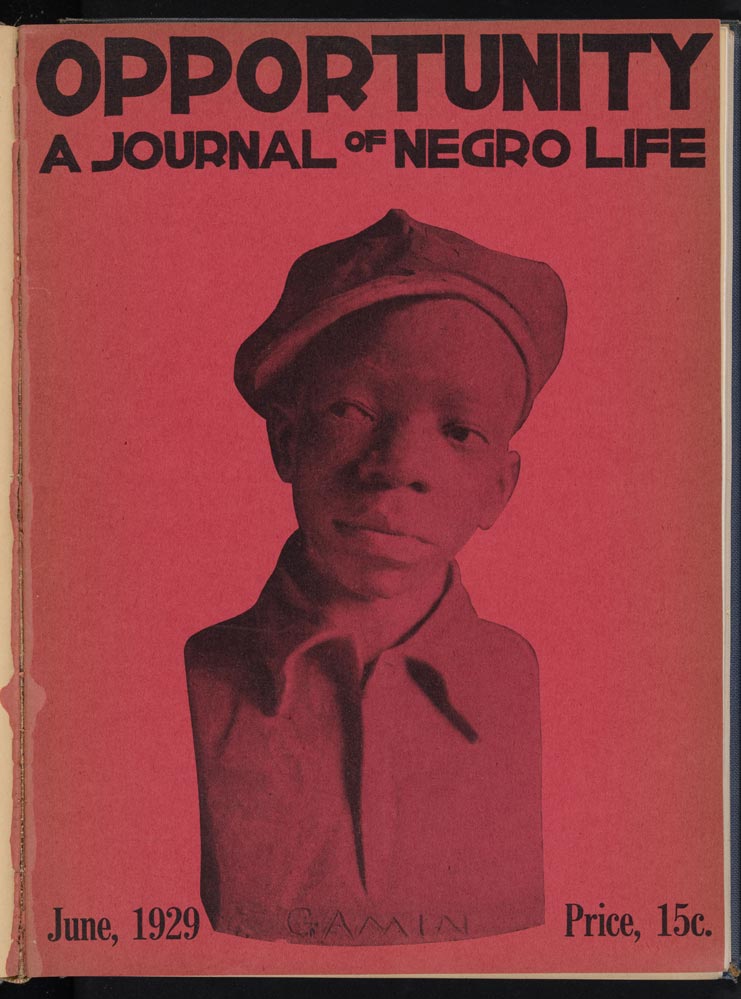

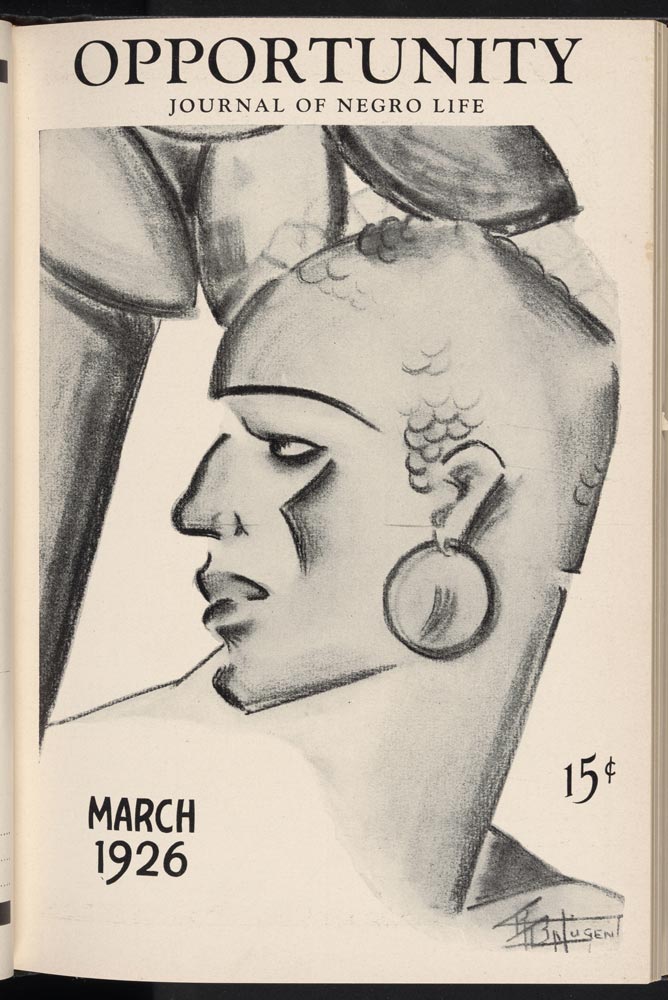

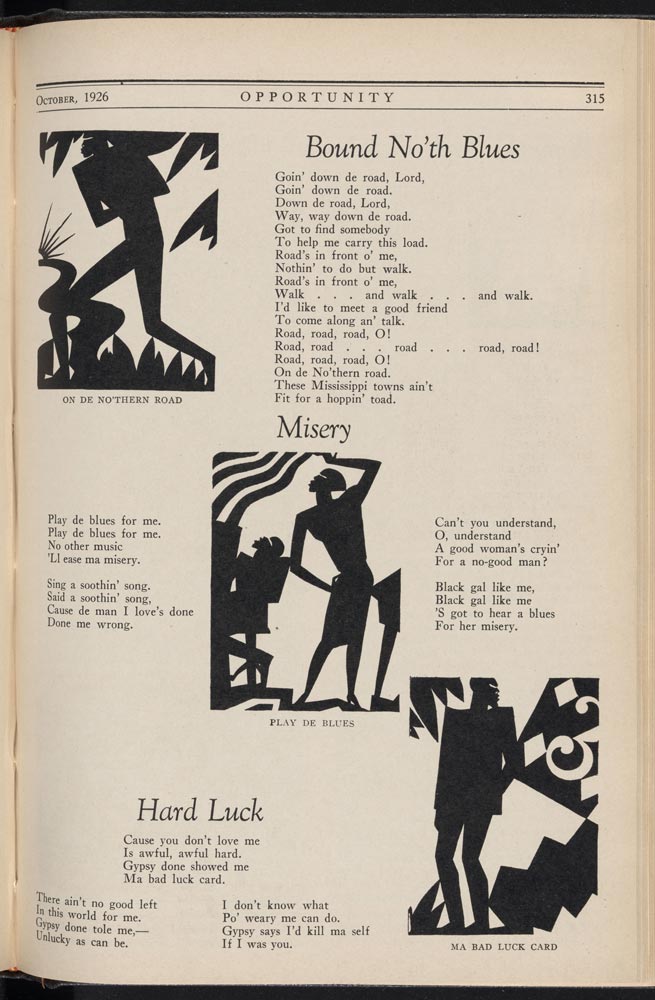

Even after the departure of founding editor Charles S. Johnson and the economic difficulties of the Great Depression, Opportunity continued to be an important outlet for research, literature, and art under its new editor, Elmer A. Carter. This was especially crucial because the nation’s economic crisis hit African American communities the hardest. The journal published important articles about labor issues, unsatisfactory conditions of public education and housing in Harlem, anti-lynching bills, the power of the Black vote in the North, and discrimination in the military. Opportunity continued to be a showcase for art and artists. Throughout its publishing run are illustrations and photographs by some of the leading visual artists of the era, such as Aaron Douglas, Winold Reiss, Miguel Covarrubias, and Richard Bruce Nugent. E. Simms Campbell, the Black cartoonist and illustrator associated with Esquire magazine, got his start with Opportunity. A twenty-three-year-old art student named Romare Bearden wrote an article, “The Negro Artist and Modern Art,” for the December 1934 issue. Bearden would become famous for his collages of Black life and is considered one of the most important African American artists of the twentieth century.

World War II created another challenge for Opportunity with wartime restrictions on paper, printing, and personnel. In 1943, it became a quarterly while still publishing writers such as Ann Petry, whose 1946 novel The Street would become the first book by an African American woman to sell over a million copies.

The National Urban League stopped publishing Opportunity at the end of 1949. As a Schomburg Center Centennial project, the complete run of Opportunity (1923-1949) is being digitized and made available on the NYPL Digital Collections website to be viewed freely, without restrictions, thanks to permission granted by the National Urban League. And in yet another serendipitous moment in our shared history, the National Urban League is planning in 2025-26 to open the Urban Civil Rights Museum, New York’s first-ever museum dedicated to civil rights, in its new Harlem headquarters. We hope to have all issues available online by the time it opens. All issues from 1923 through the late 1930s are currently accessible at digitalcollections.nypl.org.

When Schomburg passed away in 1938 at the age of sixty-four, Elmer Carter Anderson penned a tribute to him in the July 1938 issue of Opportunity:

Arthur Schomburg—His was the passion of the collector combined with the zeal of the racial crusader. … He left to posterity the Schomburg collection, worthy monument of his life work. For this alone scholars will forever owe him a debt of gratitude. To his people and to his generation he gave all of his energy, his vision, and the strength of his spirit, and more than this no man can give.

We are celebrating one hundred years of the Schomburg Center until June 2026 with a wide array of special events, exhibitions, and more to mark this milestone and continue this legacy. In the 100: A Century of Collections, Community, and Creativity exhibition, you can view many extraordinary items from the Schomburg Center’s collections and learn more about its history. You can even see a physical copy of the May 1925 issue of Opportunity. The story of this library and the community that championed it is filled with remarkable people and important achievements. One of those was Opportunity, and thanks to the Schomburg Center, you too can now explore the art, poetry, and hard-nosed journalism that can be found within its pages.